THURSDAY, 24 OCT 18:30 - 20:30 Forum Stadtpark

The danger of designing a discourse programme around the theme of "Open Everything?" is that, if you're unlucky, the discussions will end up being hijacked by ding-dong arguments over privacy.

The good thing about designing a discourse programme around the theme of "Open Everything?" is that, if you're lucky, the discussions will end up being hijacked by ding-dong arguments over privacy.

Because these arguments are not often heard outside the activist community. Sure you might sometimes meet someone whose Hotmail account got hacked (hi) or someone who stopped using Google search because they were beginning to get freaked out by the level of personalisation (hi) or someone who pettishly stands behind the cameraman at public meetings because you never know where it might end up (hi) or someone who - you get the picture - but no one in the real world (hi) really takes privacy seriously.

And for good reason. The way of the internet today is that we pay for excellent and useful services with our private data. The way we communicate with each other, by text, by voice or by video, the way we store our photos and memories, the way we learn a language, the way we find a wife - everything is free (terms and conditions may apply). What does it matter if, in return for finding out where my local Chinese takeaway is, I have to give away information about who I am, how old I am, where I live and my personal sexual preferences? I am getting something very real (chicken chow mein) in exchange for something I can't even define (privacy). And, besides, I have nothing to hide. Right?

So, as it turned out, it was not a complete disaster that a panel discussion on if and how we could make everything open ended up being a ding-dong discussion on the murky world of post-privacy.

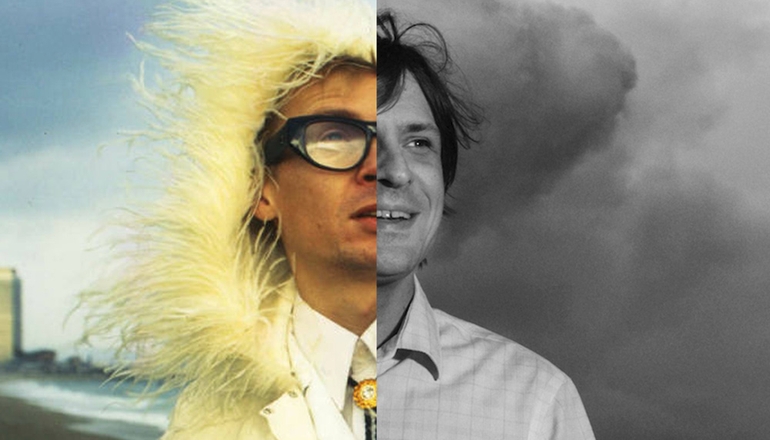

In the blue corner is Johannes Grenzfurthner (the spaceman from the opening show): "Why do we fight for civil rights? That sounds quite conservative to me." In the red corner is almost everyone else, including political activist Anne Roth: "If I disclose everything, then I give away power to others. Post-privacy only works in a world without power structures and that is a utopia."

But Johannes does have a point. "The privacy that we're trying to protect developed side-by-side with our capitalist democracy," he explains. "It is part of the bourgeousie ideology - and why should we fight for that?" He illustrates his argument by describing a typical bourgeousie household, the private domain of the all-powerful paterfamilias. In his "private" world he can do as he pleases with his wife and children, without interference from the state or meddling human rights lawyers.

This absurd illustration makes it clear that, in order to defend the private realm, we have to define the private realm. Anne Roth and Thomas Lohninger united to argue for a basic bill of rights for privacy, an agreed border between what is acceptable and what is not. "Basic rights are protective rights against the government," Anne says. "The private sphere is to fend off the government."

All well and good. But what about the positive side of openness? "When I make something public," suggests Brigitte Kratzwald, "doesn't this offer me some protection?" This is the same brand of openness that protects hearty Alpine hikers who leave details of their route with the moutain rescue service. This is the same brand of openness that contributes to freeing Prisoners of Conscience from Guantanamo Bay. This is the same brand of openness that your parents were always nagging you for: "This is where I'm going; if I disappear, please find out what's happened."

But openness by choice and openness by default are two very different things. Thomas points out that the gradual "coming out" of the lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender community over the last forty years has largely been by choice. There was no systematic process of "outing" by government or corporations. But today, our privacy choices are increasingly being made by those governments and corporations. As Johannes says: Facebook algorithms can know whether you're gay or not just from the company you keep.

Furthermore, post-privacy is only even vaguely comprehensible from a position of privilege. In Austria, it's okay to say that you are transgender. But in some parts of the world that admission could cost you your friends, your business, your liberty or even your hamster.

Perhaps, though, we are sleepwalking into a society where post-privacy is no longer a privilege, but a default setting. Jacob Appelbaum calls a mobile phone a tracking device. Needless to say, he doesn't have a mobile phone. "But if I choose not to walk around with a tracking device," he says, "then I am automatically a suspect, just because everyone else has chosen to have a tracking device." People choosing to be under surveillance has become the social norm. A teenager not on Facebook is not a teenager. Before you get too smug, grandad, the fastest growing demographic on Facebook is 45 to 54 year olds. How long before you're ostracised for being outside the post-privacy circle?

"Surveillance is an epidemic, like HIV," says Jacob Appelbaum. "Just because you weren't safe with your previous partners, doesn't mean you shouldn't start now." According to Jacob, the concept of post-privacy, where we're all supposed to be comfortable about sharing everything, is nothing more than a coping strategy for our loss of liberty - a sort of Stockholm Syndrome for Big Brother.

So what is my personal experience of this post-privacy world? Well, a couple of months ago I left Facebook, after seven years of supplying Mark Zuckerberg and the NSA with the personal information of myself and my closest friends. In a Q&A with Cullen Hoback (director of the largely depressing privacy film Terms and Conditions May Apply), I asked him the question directly: "After leaving Facebook, to what extent and for how much longer am I totally fucked?" His answer? "In perpetuity - or rather, until such a time as Facebook decide that your information no longer has any monetary value to them."

After the revelations about the hacking of Angela Merkel's phone by the NSA, no one (not even politicians) can afford to ignore the problem of surveillance and privacy any more. Unfortunately, we now all have a new problem: no solution.