“My speech was going to be very simple,” Antonino D'Ambrosio says with leather jacket Italian-American charm. “The Elevate festival is creative response, thank you.” He takes a step back off stage and smiles.

Antonino steps back, more serious. “I'd like to acknowledge the refugees who were on stage,” he adds. “Please give them a round of applause.” The applause rises again for migrants who are fighting for compassionate and humane treatment in Austria and around the EU.

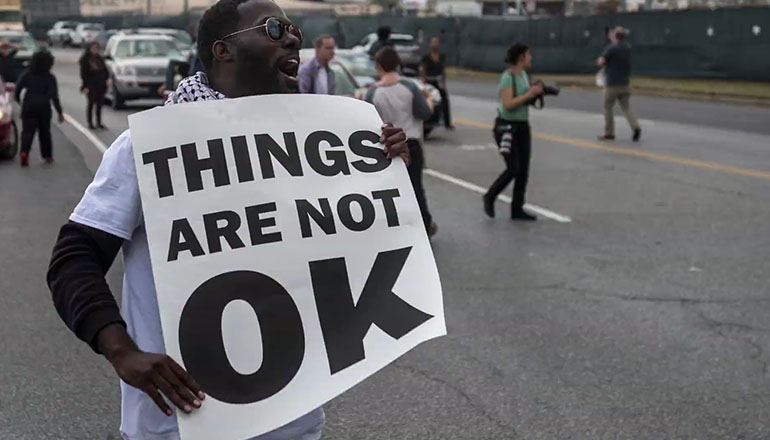

The Elevate organisers used their opening show to give a louder voice to migrant protesters who have set up a permanent camp near the police station in Graz. That voice is broadcast live on Austrian television and videostream online around the world. They'd been welcomed to the stage with the biggest round of applause of the Elevate opening night.

The refugees gave a simple speech also: “We are not from Iraq or Syria, we are just humans like you,” a young man called Hussain says. “Many of us want to serve this country as a thank you for putting us in a safe place. We can do something for this country, but we are unable under the current conditions. Please help us. We are humans, just like you.”

Back to Antonino: “This is a point that makes me fucking very angry, being an immigrant kid from the United States and seeing what's happening.” He echoes Hussain's words. “There are only one people. When you're creating situations through wars of aggression in pursuit of expanding a dying economic system and watching countries like Greece collapse, you're affecting your own people.”

For Antonino, this idea is deeply embedded in the concept of creative response, and the Elevate Festival embodies the concept perfectly: “Ideas that turn into action, actions that bring people together, [helping] people to think differently about the world around them, to remember that we are indeed one people.”

“Creative response is about reminding people that we share the human condition,” Antonino says. “And that requires storytelling.”

Antonino developed his concept of creative response as a counter to the Reagan and Thatcher ideology that was dominant when he was growing up – and that has been successful to a great degree in fostering today's political and social cynicism, the idea that “society” does not exist, that compassion is a form of weakness and that self-centred consumerism is selfless.

But Reagan and Thatcher were wrong. Compassion is not weakness; compassion is central to the human condition, central to the cooperation, coexistence and communication of families, which are the founding blocks of a society that does exist.

“Don't fight back, fight forward,” Antonino urges us. Creative response stakes out what we are for, not what are we against. Antonino uses storytelling to look back at the past, understand the present and, in the words of punk demigods The Clash, “grab the future by the face”. This leads us to the overwhelming question: “What kind of a world do you want to live in?”

That question raises a discussion over “the possible”. Slavoj Zizek, the Slovenian philosopher, notes that, in the United States, flying to or even colonising the moon is talked about as being “possible”, but decent healthcare for all or eliminating poverty is not “possible”. Here, creative response has the power to change our definitions or ideas of what is possible.

“Before I step off the stage, I want to ask you a question that Ai Weiwei had asked me: Imagine one day that the hateful world around you collapses and it is your attitude, your words and your actions that put an end to it – would you be excited?”

“This is our challenge, our creative response, our big vision of the world. Not I, not you, not them, but we. A dream that we dream together is reality. We are creative response. We own the future.”

We stand, raise our hands above our heads, join them with our neighbours. We are creative response. We own the future.