Talking About Silence

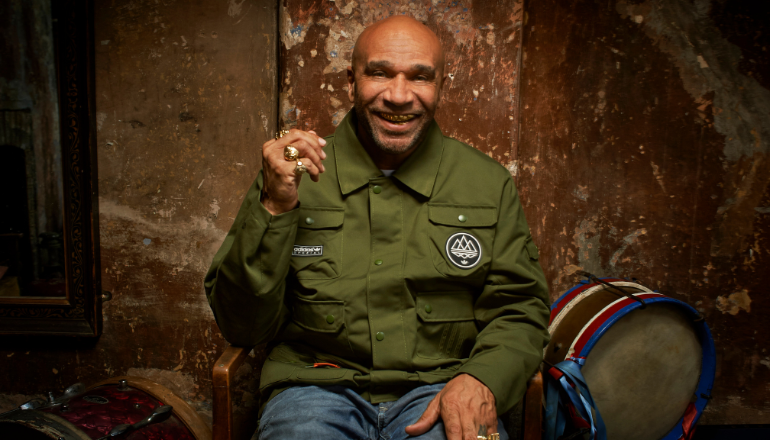

Text: Jan Skudlarek, Photo: Dirk Skiba, Translation: Phil Iroh

Also published in the new Elevate magazine out next week.

You will soon find out what all this is about. Not just yet. But soon. I promise. Until then, please treat this text with as much discretion as possible. We wouldn't want it falling into the wrong hands. That can happen faster than you think. But what does that mean? When are hands "wrong"? Good question. Smart question. But this isn't really about hands. It's about minds. Minds that know stuff.

By now you can almost consider yourself initiated. Because we're all in this together. You and me. Because we both know what it feels like. Right? Because we have it, that certain something.

That certain what? Enough is enough. Speak up now. What the hell are we talking about?

We're talking about secrets.

We're finally on the subject. But wait a minute. Isn't that a contradiction? How can we talk about secrets? As you know, secrets are what we don't talk about.

Not quite wrong, not quite right. One at a time.

What is a secret these days in a society that wants to know everything? In a society that shares everything? The answer is more than you think. Even in the era of Facebook etc. - or rather, especially in the era of Facebook etc. Every day we are confronted with the question of what we share. And what we keep. For ourselves. Alone. Or almost for ourselves. For the inner circle. It's about the art of keeping silent.

So, provisionally, we can say: the secret is what we don't share.

The possibility of constant communication forces us to rethink what we do not communicate. The demarcation between private and public is probably more topical than ever before. The unspoken still has its own magic.

Secrets are also something special in the 21st century. Literally. What we keep secret from each other is not just any knowledge. It is special knowledge. In turn, the special is to be distinguished from the ordinary. Whether we take our coffee with milk or not, doesn't have what it takes to be a secret. Hidden subject matter is rarely trivial.

Philosophically, by the way, we are facing the chicken-egg problem. Which came first? The special or the secret?

Are you keeping something secret because it's special?

Or is something special because you keep it a secret?

What is certain is that we do not hide little things that mean nothing to us. We neither want to nor have to hide them. Talking about hiding means speaking about the unspoken.

If that was too theoretical for you: It now becomes tangible. What we hide and don't hide usually has practical reasons.

This has to do with our relationship with knowledge. Because knowing doesn't just mean experiencing something - it means learning to act. If I know that you drink too much, I might not get in the car with you. If I know that you plagiarize, I'm not lending you my master's thesis. If I find out that you're a blabbermouth, I won't open my heart to you.

Secrets are therefore not only special knowledge. They are knowledge with consequence. What we know and what we don't know often affects our actions. My knowledge of whether you take your coffee with or without milk will affect whether or not I offer you milk. But it's just not special (unless you have a milk allergy, then it is).

So we are approaching a definition. There are three characteristics.

The secret is

1) non-public

2) special knowledge

1) that has consequences.

Secrets are interesting from the perspective of action theory because as a rule, we change our behaviour in the world when we experience them. This is not always the case with knowledge. When I tell you that gold in Latin is called Aurum, it's probably not a cause for action; (except in a Latin exam). But if I confess to you that I secretly have a drug problem, it would be. This knowledge changes something between us at the action level (for example, how and with whom we go clubbing with).

Because important knowledge has consequences, we care who has access to it. We have an ambivalent relationship with those who cannot keep their mouths shut. Depending on the consequences of the secret we have been told. Edward Snowden, for example, is a hero to some and a traitor to others. Anyone who thinks that Snowden's publications somehow endangered his country considers him a traitor. The point is that negative actions are feared. The other group has positive hopes for the work of Snowden and other whistleblowers. The fact that they "can't keep their mouths shut" is entirely in their own interests - because they hope that positive actions will result from these publications (for example, that secret services would start toning down the immorality).

In that sense, secrets are in style. As the ancient Greeks knew, everything flows. Today, data and information flow above all. The borderline between "shared" and "not shared" is constantly shifting. And yet, the fringes of public and private life are becoming more important than ever. Partly because we want it that way (Facebook etc.). Partly against our will - hacked computers, whistleblowers, lost cell phones. It's always about consequence. The wrong hands. About what follows.

Do you want to get in touch with the author of this text? Contact @janskudlarek on Twitter.