Ob Camouflage-Make-Up zur Vermeidung von Gesichtserkennung (CV-Dazzle, 2010) oder Geolocation-Täuschungs-Geräte (Skylift, 2016), die jedes Telefon denken lassen, sie wären in der ecuadorianischen Botschaft in London – Harvey's Arbeiten kreisen um die Themenfelder Überwachung, IT-Sicherheit und die Zukunft biometrischer Informationen im Kontext von Datenschutz. Viele Arbeiten des US-amerikanischen Medienkünstlers nutzen künstlerische Interventionen, um zwischen unsichtbaren, aber machtvollen Mechanismen und Bildern sowie deren Einfluss auf unser tägliches Leben zu vermitteln.

Für das Elevate Festival 2018 befasste sich Harvey mit genau diesen Zusammenhängen. In seiner Auftragsarbeit schafft er einen direkten Bezug zu den Begebenheit in Graz. Welche Rolle spielen Orte und Personen in Graz für die Erstellung von Überwachungsalgorithmen, die weltweit von Geheimdiensten, Sicherheitsfirmen und selbstfahrenden Autos verwendet werden? Welche Bedeutung hat die individuelle Zustimmung bei der Nutzung von Bildern im digitalen Zeitalter – ein Zeitalter, in dem Bilder ein Eigenleben führen, außerhalb unserer Kontrolle agieren und unsichtbare Technologien lenken, die wir tagtäglich nutzen?

Harvey dreht in der Arbeit „Machine Learning City“ die Perspektive um – er blickt auf die Bilder zurück, mit denen wir Maschinen zu “sehen“ lernen. Die Bilder werden der akademischen Sphäre entfremdet, in der sie sonst verortet sind – sein Projekt ist an mehreren Universitäten als Forschungsgebiet angelegt – und gleiten damit in die Kunstwelt über. Sie öffnen uns eine neue ästhetische Wertigkeit, die in den letzten Jahren als „New Aesthetic“ benannt wurde – ein Begriff, den Author und Künstler James Bridle 2011 prägte, um einer künstlerischen Strömung einen Namen zu verleihen, deren technologisierte Anmutung ein neues visuelles Regime einleitete. Die Bilder sind dabei hochpolitisch, denn sie zeigen, wie wir unsere Zukunft programmieren.

Zum Projekt in Graz, in dem sich Harvey der Frage nach dem Recht am eigenen Bild im Kontext urbaner Diskurse wie Überwachung, öffentlicher Raum und Digitalisierung widmet, spricht er im folgenden Interview mit Elevate Arts Kuratorin Berit G. Gilma. Das Interview wird in der Originalsprache wiedergegeben, um den verwendeten themenspezifischen Termini gerecht zu werden.

Berit Gilma: Tell us more about the project ‘Machine Learning City‘ that you have created for Elevate Arts 2018 and what role does the city of Graz play in it?

Adam Harvey: The project ‘Machine Learning City‘ explores the new reality of cities as datasets. But the often overlooked part of this reality is the story behind the data. How was it acquired and who might be in the dataset? ‘Machine Learning City‘ tells the story of a now famous pedestrian detection dataset, which actually originated in Graz in 2003. During the next decade, this dataset became the most widely used pedestrian detection dataset in the world. People from Vienna, Graz, as well as the neighboring city Leoben, play a unique and historic role in the ability for computers to see and understand people.

Berit Gilma: It seems this kind of databases are collections that are mainly circulating in the academic sphere, invisible to the general public. But they are powerful images of our time: they train self-driving cars and surveillance technologies like person detection or face recognition algorithms used for example by security branches of governments. What issues do you see in these databases and how do you use art to communicate them to an audience?

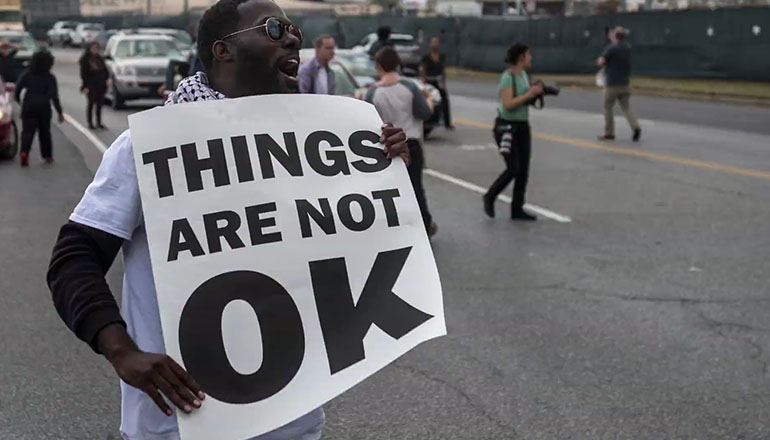

Adam Harvey: These databases also circulate widely in the commercial sphere where they are directly used for training and evaluating surveillance software that is licensed to government agencies. Although this information is public it is not widely known. Citizens aren’t aware that when they go outside and walk down the street there is a possibility that they are walking right into someone’s research project. When people are unknowingly captured for research and then distributed to surveillance companies around there world, there is a clear breach of ethics and privacy. But if we step back from these concerns, the larger issue is what does it mean to be a city engaged with machine learning? Is the public a place where algorithms can learn? If so, can other countries extract data from your city? As cities move towards further integration with artificially intelligent infrastructures will there be any limits on visual data consent?

Now as we are in the post-Snowden era, where there is more awarness about governmental surveillance, how would you say did computer vision technology change the discourse on it?

Actually, I don’t think the Snowden documents changed discourse on computer vision. The problem is that we consider visual information and signals intelligence as two separate domains when technically they are all part of the same spectrum. The significance of recent breakthroughs in computer vision capabilities is not widely understood. And as people learned from the Snowden documents, those with the means to exploit unprotected communications will have massive advantage in gathering information. Computer vision will be the biggest signals intelligence exploit of this decade.

Does computer vision change the way we navigate in the world? Or in other words, does computer vision technology influence our perception of the world?

If we reframe computer vision as a type of wireless data, then we can imagine computer vision will have as much impact as WiFi, which is to say it will have a significant impact on the way we navigate and interact with the world. Cities will have to make small adjustments to become more machine readable by autonomous vehicles, but I think the larger change will be how people become more or less machine readable. Ultimately, I think it will change the way we dress every day. This is a topic I addressed in an earlier project called CV Dazzle, a type of camouflage from computer vision.

You recently exhibited a project called ‘Megapixel: Face Database Query‘ in the Glass Room* in London where people could see if their face was in a database that trained face recognition algorithms. How many people found their faces and how was their reaction?

At least 2 people reported finding their identity in the facial recognition training database used for MegaPixels. In total the database contained about 672.000 identities and 4.7 million images. The chance of anyone finding their identity was quite low, but the facial recognition software worked surprisingly well. The database, called MegaFace, used in the project is significant because it’s used by government contractors around the world (USA, China, Russia) to train and evaluate products they license to the security and defense industry. Several of the companies publicly post their score on the MegaFace dataset website. It must be an odd feeling to realize that a random image your posted years ago on Flickr has somehow influenced the capabilities of foreign security services to find enemy combatants. Eventually the MegaPixels software will be publicly available online for anyone to use.

What is dataconsent? Where do you think is the line between the public and the private in the digital and physical sphere?

Even if a company obtains your consent, it’s often asymmetric. It’s just not possible to agree future uses of data that no one yet understands. Data consent will become a major issue as cities play host to international technology companies that require continued access to public data to ‘improve services‘. For example self-driving cars will need massive amounts of data to ensure they operate safely. To do so they will need to continuously collect and train on local data. This data may also include license plate numbers. But even if these are blurred, it’s already been proven possible to identify an automobile by the made, model, and year. In other words, you can do license plate level recognition without a license plate. This is just one of many examples where providing data consent becomes problematic. As the Strava* heat map illustrates so well, metadata can reveal a lot.

Are there potential negative outcomes if my face ends up in a database?

Right now you don’t have a choice. This is problematic because your face, which has become commoditized as a security token, could be spoofed or replicated elsewhere. It’s bad security practice to share the data that you’re also using for authentication. The other negative outcome is that current data collection practice becomes standardized or normalized to the point that you don’t actually own your face.

How much do you know about the legal situation in collecting images of person ’in the wild’?

The term ‘in the wild‘ was popularized in 2007 by the researchers who created the now famous ‘Labeled Faces in the Wild‘ dataset. This was the first time a face detection dataset had been created entirely online. In the past, researchers would have to invite people to a studio, capture their image, and acquire written consent. This also yielded unrealistic images. For computer vision algorithms to work well they need realistic data. Now this typically comes from social media sites, where users are unwittingly contributed towards building machine learning datasets that eventually train surveillance algorithms that analyze their social media images.

Images take on their own life in the digital age of the internet. In another work of yours you are using the slogan: ‘Todays selfie is tomorrow’s biometric profile‘. How do you see privacy concerns in the future with our selfie culture today?

It’s true. Selfies are helping to create incredible large biometric databases that are used to train facial recognition software that is eventually licensed back to law enforcement and government agencies. As an experiment I built a selfie image scraper in 2016 and was able to obtain 36.000 unique selfies per day from Instagram alone. We need to rethink visual privacy and the consequences of publicly posting photos. A very small image can provide a large amount of information.

Do you put your face online? How do your privacy concerns affect your daily life?

I limit what’s posted online and will ask people to remove face images. I’ve asked photographers at events to delete my image so it’s not posted online. Part of the problem is a lack of well designed tools to remove biometric information. I think there will be many opportunities for privacy enhancing technology in the next few years.

* ‘The Glass Room' war eine Ausstellung in London, die von 25.10. - 12.11.2017 stattfand und einen Einblick in die Verwendung von persönlichen Daten im digitalen Zeitalten gab. Die Ausstellung und das weitere Programm wurde von Mozilla produziert und vom Tactial Tech Kollektiv kuratiert.

* Strava ist eine Fitness-App, die im Januar 2018 unabsichtlich geheime Standorte der CIA enthüllte. MitarbeiterInnen nutzten die App, woraufhin ihre Fitnessdaten online veröffentlicht wurden. Die daraufhin abgezeichneten heatmaps an abgelegenen Orten enthüllten zum Beispiel Standorte in der Area 51 – eine geschichtsumwobene geheime Basis im US-amerikanischen Bundesstaat Nevada.

Machine Learning City

01.03. - 09.03.2018, täglich 14-19 Uhr

esc medienkunstlabor

Bürgergasse 5, 8010 Graz