THURSDAY, 24 OCT 13:30 - 15:30 Forum Stadtpark

Until October 2008, the people of Iceland were on top of the world. Capitalism worked, they thought, and they had the plasma screens to prove it. By the end of the month, the country had suffered a complete financial collapse. Nobody was ready: they were all watching their plasma screens.

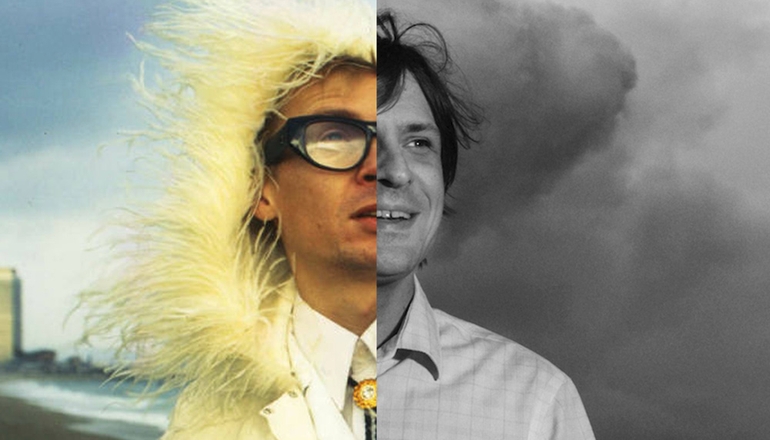

Until October 2008, Birgitta Jónsdóttir was a fringe direct democracy activist yelling into a megaphone about the ecological degradation of Icelandic fisheries or human rights in Tibet. By the end of the month, angry people of all stripes were banging on her door, asking: "How do we get megaphones?"

First dozens, then hundreds, then thousands of people turned out onto the streets, clanging together their pots and pans, demanding the resignation of parliament. The politicians pleaded with the people to return to their plasma screens, but the people would not be turned aside.

Four months later, the popular protests had brought down the government and in the subsequent elections the Citizens' Movement party won 7% of the national vote and Birgitta "accidentally" found herself the only anarchist in parliament made up entirely of leftists and led by the world's first openly gay Prime Minister.

They had one opportunity to change everything. The constitution, a half-baked document left behind by the Danes in 1944, was an obvious and ambitious target. And so the process of building the world's first horizontal constitution began.

A thousand Icelanders were randomly selected to draft the first vision of the constitution. Constitutional experts were invited to examine the ideas in this vision and published a five hundred page report on how it could be made reality. Then a constitutional council was elected: twenty-five councillors from five hundred applications.

Katrín Oddsdóttir en/discourse/year/2013/guest/oddsdottir/originally studied journalism in Dublin and once worked as a local journalist in rural Iceland, covering stories such as "Sheep Left In Field". In October 2010, now a human rights lawyer, she was elected as a member of the new constitutional council.

But the dominant political system will always try to crush anything new, "Like in a David Attenborough film," Katrín says, "where the lion is just waiting to attack." A spurious legal case was brought to declare the election invalid, on obscure technical grounds. But Birgitta's parliament pressed on and instead directly appointed the twenty-five elected councillors to a special committee, on a full-time parliamentary wage for four months.

Parliamentary business - "democracy" if you like - is usually conducted in a warlike manner, with the victors crowing over the losers: "Haha! Take that - democracy beat you!". But this constitutional council (if you haven't realised by now) was different. Katrín and the others decided to proceed by consensus. No twelve to thirteen marginal votes; it was twenty-five together or nothing.

Of course, the council was not always in total accord. Most councillors wanted no mention of the church in the constitution, but there were two priests in the council so they had to reach a compromise and ended up deferring the final decision to a public referendum.

The council embraced transparency and technology by posting weekly updates and inviting comments on the draft constitution through YouTube, Facebook and their own website. "It was like taking your clothes off," Katrín says. "But vulnerability is empowering. When you give people respect by giving them a voice, they give you respect." Comments and questions from the public were addressed and incorporated in the final draft of the new constitution.

There were one hundred and four articles (Which you can read here in English). All twenty-five councillors, complete strangers only months before, now spoke with one voice: twenty-five ayes.

"What this experiment proves is that the wisdom of the crowd is great and underestimated," Katrín says. "It's always said that people want to do things only for themselves - but it's not true." The result of the writing process was an unprecedented piece of documented hope. All that remained was to put the constitution before the people in a referendum.

But lawyers are not happy when the people make the law and parliament sat on the constitution for a year and did nothing. Politicians were nervous about an article which stipulated that only 10% of the population was required to call a national referendum; the large fishing corporations that dominate the Icelandic economy were outraged by the idea that the natural resources of the country should belong to the people, not to big business.

Finally, though, parliament was called to account and the referendum went ahead. 67% of the population agreed that these one hundred and four articles should form the basis of the new constitution. An unequivocal triumph for the new constitution and the horizontal process that had created it.

And now? "Now the parliament are trying to pretend it never happened," Katrín says. "Power always tries to maintain itself when it is accumulated in one place, like in the Icelandic parliament. It isn't going to give up easily to direct democracy."

So what happened? According to Birgitta, the leftist government made a deal with the powerful business lobbies, which totally scuppered the budding constitution. In the dying days of that parliament, Birgitta tabled a simple motion that the next parliament should honour the referendum. But no one turned up to the debate. "The media didn't give a shit," Birgitta says. "But when the next crisis comes, we'll be ready. If we had this constitution, then we would have some tools to keep the politicians honest. When the next crisis comes, then the people will realise that they need to love this constitution."

The leftist government was massacred in the polls; Birgitta retained her seat. "It's up to us," she says. "We need lots of direct democracy movements. This government will just undo what the last government did - and that's not good for the people. We need something new and we can do it."

"You can do anything if you have the will," Katrín says. "We had the will to make the drafting of the constitution open. It's bullshit to say openness is too complicated or too difficult."

"And every generation should have the right to rewrite their constitution from scratch," adds Birgitta. "It's not sacred stuff; it's about what kind of society we want to be."

"It's half time," Katrín says, with a grim smile. "We're 1-0 down, but we're going to win it."